Chennai – the capital of Madras state pre-independence and the capital of Tamilnadu post-independence. This is one of the rapidly growing cities in the new world. I visited Chennai for the first time when I was in my sixth standard. Later, it became my second home when I came there for higher studies. My intention is to take the readers into a journey across time to witness the growth of Chennai.

Firstly, the below mentioned paragraphs are not mine. They are excerpts from “The story of Madras” written by Glyn Barlow, M.A in 1921.

About the origins of Madras:

Mr. Francis Day was pleased with what he saw; for Madras is not without beauty. In those idyllic days, moreover, the Cooum river, which was known then as the Triplicane river—and which even to-day can be beautiful, although for the greater part of the year it is no more than a stagnant ditch—must have been a limpid water-way; and to Mr. Francis Day, seeing it in winter, in which season the current swollen by the rain sometimes succeeds in bursting the bar, it must have appeared almost as a noble river, rushing down to the great sea—a river such as might well have deserved the erection of a town on its banks. The negotiations were successful: but the Naik was subordinate to the lord of the soil, the Raja of Chandragiri, who was the living representative of the once great and magnificent Hindu empire of Vijianagar; and any grant that was made by the Naik of Poonamallee had to be confirmed by the Raja if it was to be made valid. Two or three miles from Chandragiri station, on the Katpadi-Gudur line of railway, is still to be seen the Rajah-Mahal, the palace in which the Raja handed to Mr. Francis Day the formal title to the land.

About Fort St.George:

From the very beginning the settlement was called Fort St. George, but it was several years before the buildings were surrounded by a high and fortified wall. It was in no spirit of military aggression that the Company’s agents enclosed their settlement with a bastioned rampart, from whose battlements big cannon frowned on all sides round.”

In 1746 there was a siege of a more serious sort. England and France were at war in Europe, and suddenly a squadron of French ships appeared off Fort St. George. After a week’s siege, the English merchants capitulated to superior force, and they were all sent to Pondicherry as prisoners, and the French flag waved over Madras; but by the treaty which ended the war, Madras was restored to the Company. Twelve years later Madras was once more besieged by the French, but unsuccessfully, and eventually the French leaders marched their forces away, quarrelling among themselves over their ill-success.

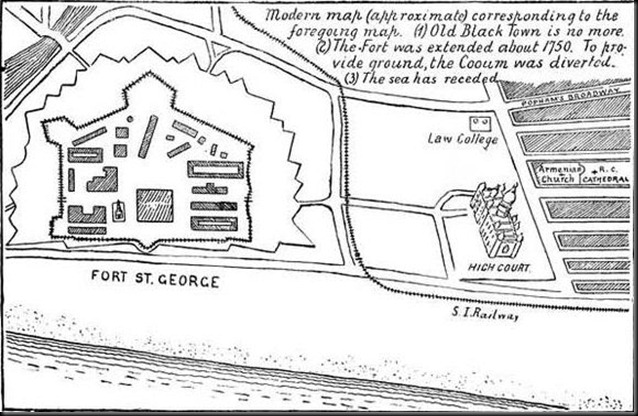

Fort St. George in the beginning was very small. Its external length parallel with the seashore was 108 yards, and its breadth was 100 yards. When White Town, which grew up around it, was fortified, there was ‘a fort within a fort’ (vide Map, p. 10); but eventually the inner wall was demolished. At various times the outer wall has been altered, but the Fort as we have it to-day is the selfsame Fort St. George nevertheless, a glorious relic of bygone times, and verily a history in stone.

About White town, Black town and Armenian Street:

The town that grew up outside the little fort was divided into two sections—’the White Town’ and ‘the Black Town.’ The boundaries of White Town corresponded roughly with what are now the boundaries of Fort St. George itself. The original Black Town—’Old Black Town’—covered what is now the vacant ground that lies between the Fort and the Law College, and included what are now the sites of the Law College and the High Court (vide Map, p. 10). The inhabitants of White Town included any British settlers not in the Company’s service whose presence the Company approved, also all approved Portuguese and Eurasian immigrants from Mylapore, and a certain number of approved Indian Christians. White Town indeed was sometimes called the ‘Christian Town.’ Black Town was the Asiatic settlement. The great majority of the original Indian settlers were not Tamilians but Telugus—written down as ‘Gentoos’ in the Company’s Records.

Armenian Street—which began as an Armenian burial-ground (vide Map, p. 10)—is an example. Armenians from Persia, like their fellow-countrymen the Parsees, have a racial gift for commerce; and Armenian merchants had been in India long before the English arrived. Enterprising Armenian merchants settled in Madras in its early days to trade with the English colonists, and the Company’s agents were glad to have as middlemen such able merchants who were in close touch with the people of the land. The most celebrated of the earlier Armenians in Madras was Peter Uscan, Armenian by race but Roman Catholic in religion, who lived in Madras for more than forty years, till his death there in 1751, at the age of seventy. He was a rich and public-spirited merchant. He built the Marmalong Bridge over the Adyar river, on one of the pillars of which a quaint inscription is still to be read, and he left a fund for its maintenance; he also renewed the multitude of stone steps that lead up to the top of St. Thomas’s Mount. His inscribed tomb is to be seen in the churchyard of the Anglican Church of St. Matthias, Vepery, which in olden days was the churchyard of a Roman Catholic chapel.

About Walltax road and SaltCotta:

The long delay in the building of the Wall was chiefly due to the fact that the representatives of the Company, being commercial men, naturally gave their chief attention to the Company’s mercantile business, and were apt to disregard the immediate necessity of expensive schemes which the Company’s military officers put forward as strategic requirements. When the Wall was first talked about, after the recovery of Madras from the French, the Directors in England, who always kept a tight hand on the Company’s purse-strings, declared that the inhabitants of Black Town ought to be made to pay for the cost of their own defences, and should be taxed accordingly; and the name of the ‘Wall Tax Road,’ which runs alongside the Central Station to the Salt Cotaurs, is a standing reminder of the Directors’ decree, while the road itself is an indication of the alignment of the western wall.

About Elihu Yale (Yale university), Chintadripet, Kaladipet, and Nyniappa Naicken street:

Elihu Yale, who was one of the early Governors of the Fort, imported some fifty weaver-families and located them in ‘Weavers’ street’, the street that is now known as Nyniappa Naick Street, in Georgetown. Some twenty-five years later, Governor Collet established a number of imported weavers in the northern suburb of Tiruvattur, in a village that was given the name ‘Collet Petta’ in the Governor’s honour—a name that degenerated into ‘Kalati Pettah’—’Loafer-land’—its present appellation. There was still a demand for more weavers, and eventually a large vacant tract was marked out as a ‘Weavers’ Town,’ under the name of Chindadre Pettah—the modern Chintadripet.

About Washermanpet:

Washermanpet is another such locality. It was not so called, as many people imagine, for being a land of dhobies (male laundresses). In the Company’s vocabulary a ‘washerman’ was a man who ‘bleached’ new-made cloth; and the Company employed a number of bleachers. The bleaching process needed large open spaces—washing-greens—on which the cloth could be laid out in the sun to be bleached; and Washermanpet covered a considerable area.

About North Madras:

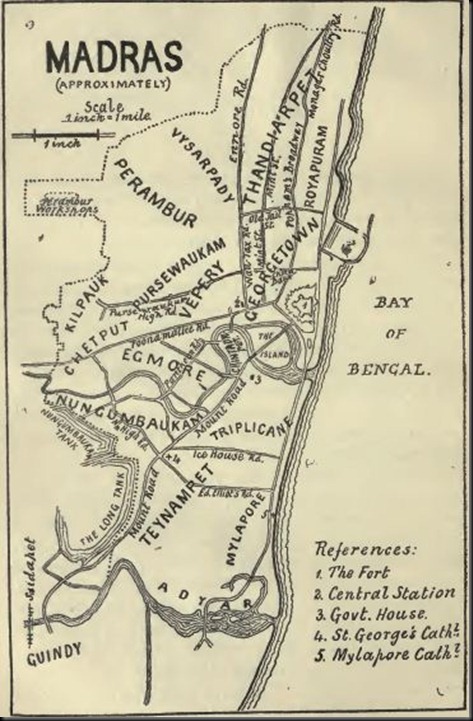

Later, in compliance with a petition by Governor Elihu Yale to the Emperor Aurangzeb, the Company received a free grant of ‘Tandore (Tondiarpet), Persewacca (Pursewaukam), and Yegmore (Egmore). Still later, in the reign of Aurangzeb’s son and successor, the village of Lungambacca (Nungumbaukam), now the principal residential district of Europeans in Madras, was granted to the Company, together with four adjoining villages, for a total annual rent of 1,500 pagodas (say Rs. 5,250). The village of Vepery—variously called in olden documents Ipere, Ypere, Vipery, and Vapery—lay between Egmore and Pursewaukam; and the Company, being naturally desirous of consolidating their territory, proceeded at once to try to obtain a grant of the place; but successive efforts on the part of Governor Elihu Yale came to naught; and it was not till much later (1742) when the Nawab of Arcot was lord of the soil, that Vepery was acquired from the Nawab.

San Thomé was acquired in 1749; and the story of the acquisition is not without interest. The names ‘San Thomé’ and ‘Mylapore’ are often used as alternative designations for one and the same locality; but in bygone days the two names represented quite different places. Mylapore was a very ancient Indian town, which seems to have been in existence long before the birth of Christ. San Thomé was a seventeenth century Portuguese settlement close by. It is an old tradition that St. Thomas the Apostle was martyred just outside Mylapore; and when the Portuguese first came to India some of them visited Mylapore to look for relics of the saint. They found some ruined Christian churches, and also a tomb which they believed to be the tomb of St. Thomas; and soon afterwards a Portuguese monastery was established on the spot. A Portuguese town grew up around the monastery; and in course of time the town became a commercial centre, and was surrounded with a fortified wall, and was the Portuguese settlement of San Thomé, over against the Indian town of Mylapore. An Italian dealer in precious stones who visited India in the sixteenth century wrote of San Thomé that it was ‘as fair a city’ as any that he had seen in the land; and he described Mylapore as being an Indian city surrounded by its own mud wall. Mylapore was thus in effect the Black Town of San Thomé; but in later days the two towns were combined. When the English came to Fort St. George, the power of the Portuguese was already waning; and the development of the influence of the English at Madras meant a further lessening of the influence of the Portuguese at San Thomé; and it was a natural consequence that San Thomé, including Mylapore, became a prey to successive assailants.

About Leith castle in San-Thome:

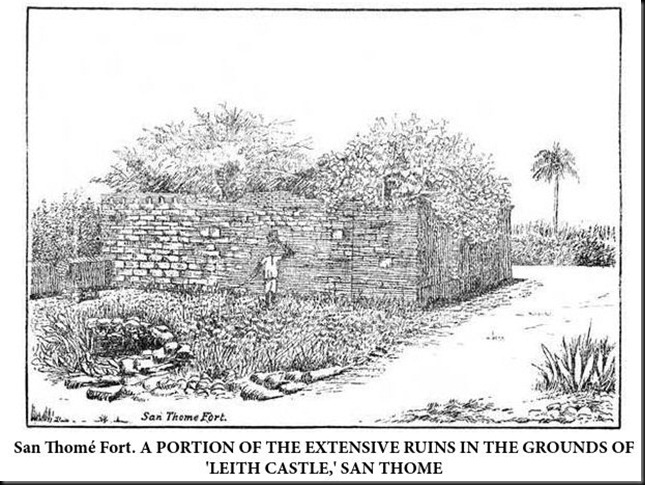

The remains of the San Thomé Redoubt stand within the grounds of ‘Leith Castle,’ a house that lies south of the San Thomé Cathedral. The remains are ruins, but the massive walls fifteen feet high and three feet thick, are suggestive of the purpose for which the redoubt was built. The ‘Records’ show that the San Thomé Redoubt, built in 1751, was a very complete fortification, with a moat forty feet wide, a glacis, and all the other works that are usual in respect of a well appointed building of the kind.

The Egmore Redoubt was a good deal older than that of San Thomé. It was constructed in the days of Queen Anne. It was intended, of course, for the special protection of Egmore; but in those distant days when trips to the hills were unknown, even Egmore was a health-resort in respect of the crowded Fort St. George, and it was officially reported that the Egmore Redoubt might ‘serve for a convenience for the sick Soldiers when arrived from England, for the recovery of their health, it being a good air.’

About Pachaiyappa College:

Pachaiyappa’s College, a well-known Hindu institution, had its first beginning in 1842. Like the other colleges in Madras, it began as a school; the school was called ‘Pachaiyappa’s Central Institution,’ and was located in Black Town. The present buildings were opened in 1850 by Sir Henry Pottinger, an ex-governor of Madras, amid a large gathering of leading European and Indian residents; and for a number of years the annual ‘Day’ at Pachaiyappa’s College was an important social event. Pachaiyappa was a rich and religious Hindu, who made his money as a broker in the Company’s service, and who died more than a hundred years ago leaving a lakh of pagodas – some 3½ lakhs of rupees – for temple purposes. The trustees neglected the provisions of the will, whereupon the High Court assumed control of the funds, which under the Court’s control rose to the value of nearly Rs. 7½ lakhs. The original amount was set apart for the fulfilment of the terms of the will, and the surplus was assigned to educational purposes in Pachaiyappa’s name.

About St.Andrew’s Kirk:

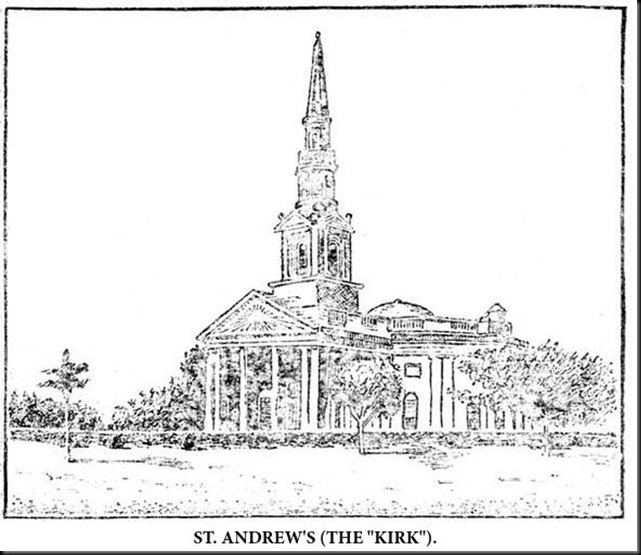

St. Andrew’s Church—most commonly known as ‘The Kirk’—was planned while St. George’s was being built; and it is remarkable that it was not projected sooner than it was. Scotchmen in Madras, as in other parts of India, apart from Scottish soldiers, have been many; and the names of a number of Madras roads and houses—such as Anderson Road, Graeme’s Road, Davidson Street, Brodie Castle, Leith Castle, Mackay’s Gardens—are reminders of the fact that not a few of the Scots of Madras have been influential; and at the time when a second Anglican church was being built in the city it was suggested to the Directors of the Company in England that the numerous residents who were members of the Church of Scotland ought to have a church too. The Directors, who realized no doubt the desirability of being agreeable to the many Scots in Madras, one of whom at the time was the Governor himself, Mr.Hugh Elliot, consented to the suggestion, and in 1815 they sent out a notification that a Presbyterian church was to be built not only at Madras but also in each of the other Presidency cities at the Company’s expense, and that the Company would maintain a Presbyterian chaplain at each. The Directors laid down no instructions as to what was to be the maximum cost of each kirk, but it was unpretentious buildings that they had in mind. At Bombay a large kirk was built for less than half a lakh of rupees, but for the kirk at Madras the Madras Government submitted a bill for nearly Rs.2¼ lakhs – some Rs.10,000 more than the total cost of St.George’s Cathedral, and the Directors were indignant. The Kirk, however, had been built; and it is one of the handsome churches of Madras. It is a domed building, with a tall steeple over the Grecian façade; and some of its critics have said that the combination of dome and steeple gives the edifice a strangely camel-backed appearance; but, however that may be, the dome adds beauty to the interior. When the Church was opened, it was found that the dome evoked disturbing echoes, and a large additional expense had to be incurred to exorcise the wandering voices. The steeple reaches a height of 166½ feet, which is 27½ feet higher than that of St.George’s.

The final word’s of the author:

But the greatest charm of Madras lies in its history. It was here that the foundations of the Indian Empire may be said to have been laid. The history of Madras is not a story of aggressive warfare. The settlers were gentle merchants, whose weapon was not the sword but the pen, and whose only desire it was to be left alone to carry on their business in peace. But the rising city was a continual mark for the hostility of commercial and political rivals, both European and Indian. It was a storm-centre, and the storms were often fierce; and the merchants were often compelled to meet force with force. Moreover, the merchants were men, and their doings therefore were by no means always without reproach; but, with due allowance for human weakness, the history of Madras is a history of which Madras may be proud. The city has grown from strength to strength, and in its story there is much inspiration. This little book has merely told the story in part; but it will have served its purpose if it has in any way helped the reader to realize that the story of Madras is the story of no mean city.

I guess I don’t have to say more. I hope you would have enjoyed reading and visualizing. For those of you who are interested to read the entire book, please click here – The Story of Madras by Glyn Barlow. M.A.